The nocturnal mouse lemurs (genus Microcebus) are the tiniest primates in existence. Two species of mouse lemurs were known in 1990, one in the dry woodlands of western and southern Madagascar as well as one in the eastern rainforests. However, at present several more species have been discovered. In this article, we will look into the morphology, habitat behaviour and other peculiar features of the mouse lemurs in detail.

- Evolution of the lemur species

- Scientific classificaiton

- Different species of mouse lemurs

- Morphology

- Sexual dimorphism in mouse lemurs

- Movement

- Habitat

- Social organization

- Activity levels of mouse lemurs

- Behaviours

- Diet

- Reproduction

- Status of conservation

- Threats to the mouse lemur species

- IUCN red list data on mouse lemurs

- FAQs

Evolution of the lemur species

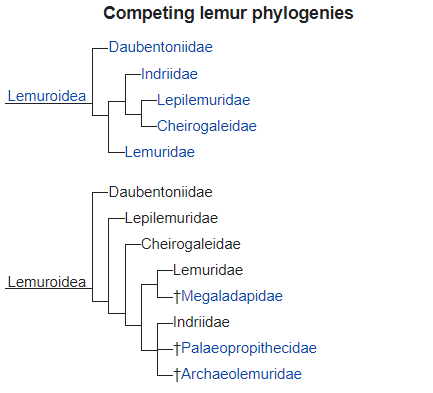

Since their arrival in Madagascar, lemurs have evolved considerably. According to molecular analyses, there have been two significant periods of diversification from which all known current, as well as extinct family lineages, have originated.

The first diversification

During the first phase, which took place between the Late Eocene (42 million years ago) and the Oligocene (42 million years ago) (30 mya), global cooling occurred and changes in ocean currents affected weather patterns. These erratic changes led to the divergence of lorisoid primates as well as the five major clades of squirrels, all of which occupy niches comparable to lemurs. However, there is some debate as to which species diverged first. Some scientists argue that Cheirogaleidae and Lepilemuridae diverged the earliest, while others believe that the Indriidae and Lemuridae were the first to diverge.

The second diversification

The second major period of diversification occurred during the Late Miocene, between 8 and 12 million years ago, and includes the real lemurs (Eulemur) as well as mouse lemurs (Microcebus). This occurrence corresponded with the start of the Indian monsoons, the last big shift in Madagascar’s climate. In fact, when humans arrived on the island some 2,000 years ago, the populations of both true and mouse lemurs were considered to have separated owing to habitat fragmentation.

The mouse lemurs look similar to one another. True lemurs, on the other hand, are more easily distinguished and display sexual dichromatism. Understanding their phylogeny and diversity has also benefited from research in karyology, molecular genetics, as well as biogeographic patterns. True lemurs are frequently diurnal, allowing possible mates to readily identify one another as well as other related species. In contrast, mouse lemurs are nocturnal, limiting their capacity to exploit visual signals for mating selection. Instead, they rely on smell as well as aural cues. Lastly, true lemurs may have acquired sexual dichromatism as a result of these factors, whereas mouse lemurs may have evolved to be cryptic species.

Phylogenetic-tree-of-all-lemur-species-used-for-Phylogenetic-comparative-analyses-in-this-convertedScientific classificaiton

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Mammalia |

| Order | Primates |

| Suborder | Strepsirrhini |

| Family | Cheirogaleidae |

| Genus | Microcebus |

Different species of mouse lemurs

Microcebus taxonomy is relatively active, with 10 new species described since 2000. Groves (2005) mentions eight species in the genus, however, several more species have been reported since his publication and are all listed below as complete species.

| Common name | Scientific name |

| Arnhold’s mouse lemur | M. arnholdi |

| Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur | M. berthae |

| Bongolava mouse lemur | M. bongolavensis |

| Boraha mouse lemur | M. boraha |

| Danfoss’ mouse lemur | M. danfossi |

| Ganzhorn’s mouse lemur | M. ganzhorni |

| Gerp’s mouse lemur | M. gerpi |

| Reddish-grey mouse lemur | M. griseorufus |

| Jolly’s mouse lemur | M. jollyae |

| Jonah’s mouse lemur | M. jonahi |

| Goodman’s mouse lemur | M. lehilahytsara |

| MacArthur’s mouse lemur | M. macarthurii |

| Claire’s mouse lemur | M. mamiratra, synonymous to M. lokobensis |

| Bemanasy mouse lemur | M. manitatra |

| Margot Marsh’s mouse lemur | M. margotmarshae |

| Marohita mouse lemur | M. marohita |

| Mittermeier’s mouse lemur | M. mittermeieri |

| Gray mouse lemur | M. murinus |

| Pygmy mouse lemur | M. myoxinus |

| Golden-brown mouse lemur | M. ravelobensis |

| Brown mouse lemur | M. rufus |

| Sambirano mouse lemur | M. sambiranensis |

| Simmons’ mouse lemur | M. simmonsi |

| Anosy mouse lemur | M. tanosi |

| Northern rufous mouse lemur | M. tavaratra |

Morphology

Mouse lemurs are the smallest primates, with a combined head, body, and tail length of less than 27 cm. Furthermore, they are classified into two categories based on the colour of their total fur. M. murinus and M. griseorufus are grey in colour, while M. rufus, M. ravelobensis, M. myoxinus, M. berthae, M. sambiranensis, M. tavaratra, M. lehilahytsara, M mittermeieri, M. jollyae, as well as M. simmonsi are reddish in colour. However, certain species are difficult to classify merely by observation, and such species are differentiated from one another based on genetic variations as well as body measures. Additionally, there is significant intra-species variation in colouring in certain organisms, which confuses matters even further. In fact, in some cases, specimens with extremely diverse colouration have turned out to be the same species when examined using other methods.

Specific morphology of different species

| Species | Morphology |

| M. lehilahytsara | Is brilliant maroon in colour, with a pale abdomen as well as an orangeish back, head, and tail. |

| M. rufus | Has a greyish-brown back with a black stripe, reddish arms, a greyish-white belly, as well as a reddish head. |

| M. mittermeieri | Has a red-brown or rust-coloured head and back, as well as some orange on its limbs and a white-brown abdomen. |

| M. jollyae | Has a reddish-brown back and head with a grey abdomen. |

| M. simmonsi | Has a greyish white ventrum and dark reddish or orange-brown fur on its back, arms, as well as head. |

| M. bongolavensis and M. danfossi’s | The hue of the heads of both the species vary according to the individual, but the back is orangish maroon and the abdomen is creamy-white. |

| M. mamiratra | The back and tail of the animal is pale reddish-brown, with a white or cream ventrum. |

| M. tavaratra | Is distinguished by a reddish head, a dark brownish back, and a whitish-beige abdomen. |

| M. sambiranensis | Has a whitish-beige ventrum and a reddish back with a faintly defined stripe. |

| M. ravelobensis | The back of the organism is golden-brown or mottled-red, with a yellow to white belly and a brown tail. |

| M. murinus | The back is greyish-brown with a beige or grey belly and a stripe along the back. |

| M. myoxinus | Has a reddish-brown back with a dorsal stripe and reddish-brown markings on the head. |

| M. berthae | Is reddish in colour, with a dorsal line and a brighter head than the rest of its body. |

| M. griseorufus | Has a grey back with a cinnamon-brown stripe, the head has reddish markings, and the belly is white. |

Sexual dimorphism in mouse lemurs

In M. myoxinus , the body is not sexually dimorphic, but there is a seasonal flip of dimorphism between men and females, with males consistently heavier than females during the reproductive season, while the opposite is true the rest of the year. M. murinus also exhibits a comparable seasonal change in sexual dimorphism in mass. On the other hand, M. rufus, M. berthae as well as M. murinus do not exhibit sexual dimorphism in body size.

Movement

All mouse lemurs use four feet for walking, which includes sprinting, but also short distance leaping as well as some movement on the ground. However, some changes in locomotion have been observed amongst mouse lemur species. M. ravelobensis, for example, travels through its habitat by leaping, but M. murinus is mostly on four feet, the variations are likely owing to changes in body form as well as preferred forest layers.

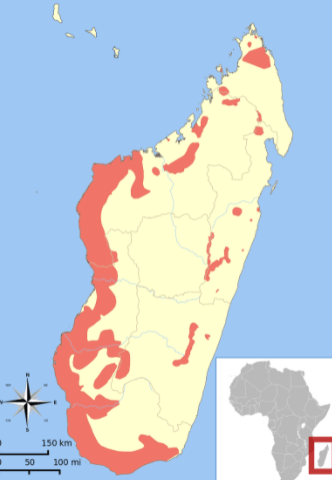

Habitat

Mouse lemurs, like all other lemurs, are found only in Madagascar, an island off the eastern coast of Africa. Among the reddish and greyish forms, reddish species (M. rufus, M. ravelobensis, M. myoxinus, M. berthae, M. sambiranensis, M. tavaratra, M. lehilahytsara, M. mittermeieri, M. jollyae, as well as M. simmonsi) have smaller geographical ranges. However, species distributions need to be investigated further and are only partially understood.

Mouse lemurs call various sorts of forest environments on Madagascar home, including human-modified forests. Evergreen littoral, dry deciduous, arid spiny, sub-arid thorn scrub, thick scrub, spiny, mangrove, sub-humid, partly evergreen, lowland, lowland as well as montane tropical humid are the forest types in which several species of mouse lemur may be found. They have also been discovered in ancient eucalyptus forests with dense undergrowth. Some species are found in many habitat types, while others are only found in one.

Social organization

Although they forage alone, mouse lemurs live in a scattered yet sophisticated social structure and are not lonely. Additionally, within this scattered multi-male or multi-female system, there are social ties in which individual mouse lemurs may identify as well as form relationships with other mouse lemurs. This is demonstrated by regular contacts with members of the same species, as well as consistent sleeping groups.

For example, M. murinus appears to be the most gregarious of the mouse lemurs having been observed in close vicinity with other members of the species 96 times out of the 100 hours of observation. Additionally, the female members of the species are regularly found in close proximity throughout the night.

Sleeping groups

In mouse lemurs, sleeping groups constitute the most basic social unit. While mouse lemurs are frequently found alone at night, in communal sleeping areas, they are often seen with others, but this varies depending on species as well as season. For example, M. murinus sleeping groups can have up to 16 individuals, but M. rufus sleeping groups typically comprise 1 to 5 individuals.

Furthermore, females of M. murinus, for example, frequently sleep at sleeping places with a regular group of other females, but males normally sleep alone. M. ravelobensis as well as M. berthae establish sleeping groups that include both sexes. On the other hand, M. myoxinus do not form sleeping groups and prefer to sleep alone.

These distinctions highlight variance among mouse lemurs in relation to one another, yet overall, the same basic scattered social order prevails.

Activity levels of mouse lemurs

In mouse lemurs, there are two forms of torpor or moments of lethargy: daily as well as seasonal. Daily torpor aids in energy management, whereas seasonal torpor aids mouse lemurs in surviving yearly periods of resource constraint. However, not all mouse lemurs sleep through the winter.

During torpor and hibernation, metabolic rate, as well as body temperature decrease. In fact, the mouse lemur’s metabolism falls by up to 90% and body temperature to almost that of the surrounding environment.

Behaviours

Mouse lemurs engage in a wide range of social behaviours. Grooming and huddling are observed at the beginning as well as at the conclusion of the night, so are other activities such as chasing and fighting. Most M. ravelobensis social contacts are not violent, and those that generally occur just before mating season.

Female dominance over male animals has been shown in M. berthae, as well as in captive M. murinus, while male dominance is observed in all other species.

Diet

All species of mouse lemurs have a diverse diet, which changes depending on the season. Gums, and other sugary discharge of insects, are vitally essential in the diets of mouse lemurs, especially those living in dry woodlands. A seasonal shift in the diet of the mouse lemur is seen near the conclusion of the rainy season and the early succeeding dry season when there is a large rise in the number of varieties as well as amounts of fruits consumed.

M. murinus, for example, consume insect secretions, arthropods, tiny vertebrates, gum, fruit, flowers, nectar, as well as leaves and buds. M. rufus as well as M. ravelobensis have diets that are comparable to M. murinus diet. M. rufus diet consists of 64 different kinds of fruit as well as members of 9 different insect groups. Furthermore, the fruit of the mistletoe was discovered to be a diet staple for the species and a key meal utilised to get through periods of resource constraint. M. berthae‘s diet is unknown, however, early evidence suggests that the species consumes largely animal debris and insect secretions.

Reproduction

Mouse lemurs limit mating to specified periods of the year, typically between September and January. Furthermore, seasonal fluctuations in the length of sunshine stimulate reproductive activity in mouse lemurs. However, this may not always be the case. M. zaza, for example, is one of the few mouse lemur species that breed aseasonally.

Although, there is heterogeneity between and within species in the duration as well as temporal commencement of breeding. During the breeding season, both sexes’ genitals undergo changes in structure. Male testes grow to a significant size during the start of the mating season. The female vagina is closed except during the reproduction cycle and birth. The vagina also changes colour and shape at the start of each estrus cycle. Additionally, female mouse lemurs can have more than one estrus cycle throughout the mating season. M. rufus females in the wild, for example, have 2.5 estrus cycles every reproductive season, each lasting 59 days, while female M. murinus go through 2.25 cycles every season, each lasting 52 days.

Hence, mouse lemurs are best described as wild, although their mating procedures are unknown. Both scramble competition, as well as contest competition, have been observed in the species.

M. berthae‘s mating mechanism, for example, suggests scramble competition, while M. murinus mates in most situations, but not always, within the context of scramble competition polygyny. They exhibit different mating systems as a result of the various environments in which they reside.

Status of conservation

While some mouse lemur species are widespread, the identification of increasing diversity indicates that certain species are present only in limited regions or locales, raising the likelihood that local habitat changes, as well as degradation, may gravely threaten their existence. As a result, the danger levels of mouse lemurs must be reassessed, and the situation of certain species may be worse than previously thought.

Threats to the mouse lemur species

1. Human-caused habitat loss and degradation is a threat.

Human activities have the potential to harm mouse lemurs by deteriorating or destroying habitats, particularly through slash-and-burn agriculture, logging, charcoal manufacturing, commercial maize farming, brush fires, firewood gathering, and sapphire mining. For example, locals logged trees utilised by mouse lemurs at the Beza Mahafaly Special Reserve in southwest Madagascar, as well as exploited them for honey collection. Furthermore, forests degraded for livestock grazing and slash-and-burn agriculture also cause loss of species. In fact, slash-and-burn agriculture is the primary danger to the lemurs in Marojejy Strict Nature Reserve in northeast Madagascar.

Forest degradation has the potential to both enhance competition and disrupt the ecological balance of sympatric mouse lemur species. Deforestation may modify habitats in such a way that one species of mouse lemur may hasten the extinction of another sympatric species of mouse lemur. Some mouse lemur species rely on tree-hole nests for torpor and newborn rearing, but forest deforestation has the potential to change the availability of appropriate resting locations for the species, thus, threatening their existence.

Although mouse lemurs may be found in secondary forests, their body mass and population are lower in some of these habitats because there is less food available, fewer individuals enter torpor, and there are fewer suitable sleeping locations. Therefore, they are not ideal for the species.

2. Alien species pose a threat

Feral cats and dogs, for example, constitute an additional predation hazard to M. ravelobensis.

3. Hunting or gathering

M. murinus is occasionally captured as a pet. It is not recommended as they are very violent when they reach puberty.

IUCN red list data on mouse lemurs

18 out of 24 recognized mouse lemur species are considered threatened as of 2013, however, this list has grown since. The threatened species are as follows:

| Common name | Taxon | Red list status | Date last updated |

| Arnhold’s Mouse lemur | Microcebus arnholdi | Vulnerable | May 9, 2018 |

| Madame Berthe’s Mouse lemur | Microcebus berthae | Critically Endangered | December 13, 2019 |

| Danfoss’ Mouse lemur | Microcebus danfossi | Vulnerable | May 9, 2018 |

| Bongolava Mouse lemur | Microcebus bongolavensis | Endangered | May 9, 2018 |

| Grey-brown Mouse lemur | Microcebus griseorufus | Least Concern | August 2, 2018 |

| Boraha Mouse lemur | Microcebus boraha | *Data Deficient* | December 11, 2019 |

| Ganzhorn’s Mouse lemur | Microcebus ganzhorni | Endangered | November 10, 2019 |

| Gerp’s Mouse lemur | Microcebus gerpi | Critically Endangered | July 11, 2012 |

| Jolly’s Mouse lemur | Microcebus jollyae | Endangered | May 9, 2018 |

| Goodman’s Mouse lemur | Microcebus lehilahytsara | Vulnerable | May 7, 2018 |

| Marohita Mouse lemur | Microcebus marohita | Critically Endangered | July 1, 2012 |

| Simmons’ Mouse lemur | Microcebus simmonsi | Endangered | May 9, 2018 |

| MacArthur’s Mouse lemur | Microcebus macarthurii | Endangered | May 9, 2018 |

| Claire’s Mouse lemur | Microcebus mamiratra | Endangered | May 9, 2018 |

| Bemanasy Mouse lemur | Microcebus manitatra | Critically Endangered | May 9, 2018 |

| Mittermeier’s Mouse lemur | Microcebus mittermeieri | Endangered | May 9, 2018 |

| Margot Marsh’s Mouse lemur | Microcebus margotmarshae | Endangered | May 9, 2018 |

| Grey Mouse lemur | Microcebus murinus | Least Concern | April 5, 2020 |

| Peters’ Mouse lemur | Microcebus myoxinus | Vulnerable | July 11, 2012 |

| Sambirano Mouse lemur | Microcebus sambiranensis | Endangered | May 9, 2018 |

| Anosy Mouse lemur | Microcebus tanosi | Endangered | August 14, 2018 |

| Golden-brown Mouse lemur | Microcebus ravelobensis | Vulnerable | May 9, 2018 |

| Rufous Mouse lemur | Microcebus rufus | Vulnerable | May 7, 2017 |

| Sambirano Mouse lemur | Microcebus sambiranensis | Endangered | May 9, 2018 |

| TavaratraꢀMouse lemur | Microcebus tavaratra | Vulnerable | May 7, 2018 |

FAQs

1. Is a mouse lemur a mouse?

No, the numerous lemur species are not categorised as rodents. In fact, Microcebus, derives from the Greek words mikros, meaning “small”, and kebos, meaning “monkey”.

2. Is it possible to keep a mouse lemur as a pet?

Despite the fact that their huge eyes, as well as tiny ears, make them cute to many people, mouse lemurs do not make suitable pets. This is because of three reasons. Firstly, although they are rather docile as children, they become vicious as they reach maturity and are not afraid to bite and fight humans. Furthermore, because females are the dominant gender in lemur cultures, they are more hostile. Secondly, another reason why they do not make good pets is the lack of medical care. This is because mouse lemurs are an unusual species and there are only a few veterinarians who can treat them if they become ill or wounded. Lastly, they are endangered, thus, making it unlawful to own them.

3. How expensive are mouse lemurs?

Mouse lemurs are ten times less expensive to rear than certain other primates, costing roughly $1,200 against over $15,000 for the common marmoset.

4. Is it possible for a mouse lemur to be venomous?

No, mouse lemurs are not poisonous.

5. Why are mouse lemurs used in a scientific study?

Mouse lemurs offer immense promise for primate biology, behaviour, and conservation. In the same way as fruit flies and mice have altered our understanding of developmental biology and many other areas of biology and medicine over the last 30 or 40 years. Hence, they are used as an ideal model primate organism to study areas like ageing, behaviour, the study of cardiovascular diseases as well as neuroscience (because they develop an Alzheimer’s-like illness with plaques in the brain identical to those observed in human patients).

Share with your friends