In this article, we are going to have a look at everything that is related to Aesop and his fables!

Who is AESOP?

Aesop was a Greek sensationalist and narrator credited with various tales currently aggregately known as Aesop’s Fables. Although his reality stays indistinct and no compositions by him make due, various stories credited to him were assembled across the hundreds of years and in numerous dialects in a narrating custom that proceeds right up ’til the present time. Large numbers of the stories related to him are portrayed by human creature characters.

Dispersed subtleties of Aesop’s life can be found in antiquated sources, including Aristotle, Herodotus, and Plutarch. An antiquated scholarly work called The Aesop Romance tells a roundabout, likely exceptionally fictitious variant of his life, including the conventional portrayal of him as a strikingly revolting slave who by his keenness procures opportunity and turns into a counsel to rulers and city-states. More seasoned spellings of his name have included Esope and Isope. Portrayals of Aesop in mainstream society in the course of the most recent 2,500 years have included many things of beauty and his appearance as a person in various books, movies, plays, and TV programs.

PDF – https://memory.loc.gov/service/gdc/scd0001/2013/20131001005ae/20131001005ae.pdf

AESOP’S Life

The most punctual Greek sources, including Aristotle, demonstrate that Aesop was welcome into the world around 620 BCE. This was in the Greek state of Mesembria. Various later authors from the Roman supreme period say that he was welcome into the world in Phrygia.

From Aristotle and Herodotus, we discover that Aesop was a slave in Samos. His lords were also initial a man named Xanthus and afterwards a man named Iadmon; that he should ultimately have been liberated because he contended as a supporter for an affluent Samian; and that he met his end in the city of Delphi. Plutarch lets us know that Aesop had come to Delphi on a strategic mission from King Croesus of Lydia, that he offended the Delphians, was condemned to death on an exaggerated charge of sanctuary burglary and was tossed from a bluff (after which the Delphians endured epidemic and starvation).

What About The Past?

Before this lethal episode, Aesop met with Periander of Corinth, where Plutarch makes them feast with the Seven Sages of Greece, sitting alongside his companion Solon, whom he had met in Sardis. (Leslie Kurke recommends that Aesop himself “was a famous competitor for incorporation” in the rundown of Seven Sages.)

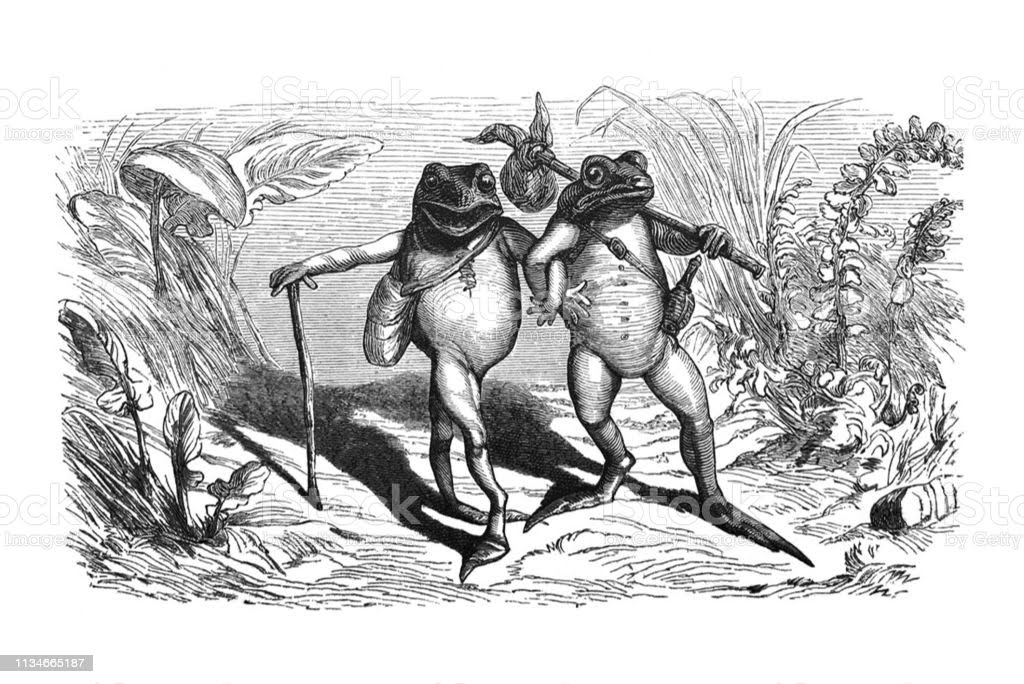

Issues of ordered compromise dating the demise of Aesop and the rule of Croesus drove the Aesop researcher (and compiler of the Perry Index) Ben Edwin Perry in 1965 to infer that “everything in the antiquated declaration about Aesop that relates to his relationship with one or the other Croesus or with any of the supposed Seven Wise Men of Greece should be figured as scholarly fiction,” and Perry moreover excused Aesop’s passing in Delphi as legendary; however ensuing exploration has set up that a potential political mission for Croesus and a visit to Periander “are predictable with the extended period of Aesop’s death.” Still tricky is the story by Phaedrus which has Aesop in Athens, telling the tale of the frogs who requested a ruler, during the rule of Peisistratos, which happened a very long time after the assumed date of Aesop’s passing. Fascinating, is it not?

Also, Read Movies to Watch When Looking for Motivation

What are Fables?

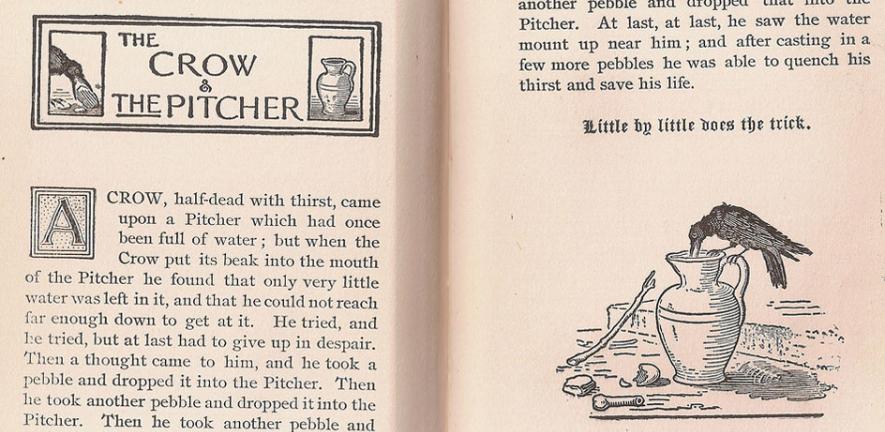

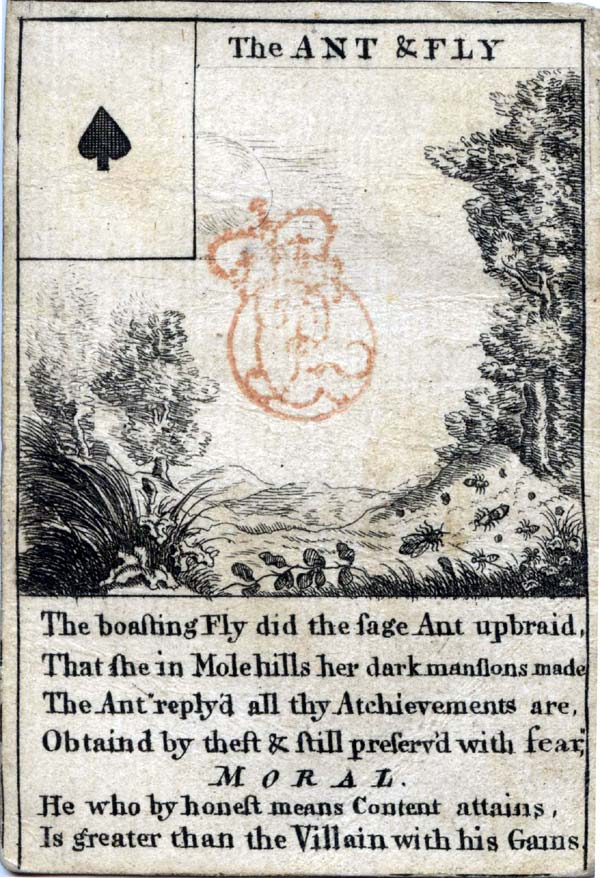

The fable for the most part includes creatures that act and talk as people, told to feature human imprudence and shortcomings. A moral-or illustration for conduct is woven into the story and regularly unequivocally planned toward the end. The Western practice of tale viably starts with Aesop, a possible unbelievable figure to whom is credited an assortment of old Greek tales.

Present-day releases contain up to 200 tales, however, there is no chance of following their genuine beginnings; the soonest realized assortment connected to Aesop dates to the fourth century BCE. Among the Classical creators who fostered the Aesopian model were the Roman artist Horace, the Greek biographer Plutarch, and the Greek humorist Lucian. Fable prospered in the Middle Ages, as did all types of moral story, and a remarkable assortment of tales was made in the late twelfth century by Marie de France.

The middle-aged tale led to an extended structure known as the monster epic-an an extensive, long-winded creature story packed with saint, miscreant, casualty, and an unending stream of brave undertaking that mocked epic magnificence. The most well-known of these is a twelfth-century gathering of related stories called Roman de Renart; its legend is Reynard the Fox (German: Reinhart Fuchs), an image of tricky.

Interesting Facts About Aesop’s Fables

Two English artists adjusted components of the monster epic into long sonnets: in Edmund Spenser’s Prosopopoia; or, Mother Hubbard’s Tale (1591) a fox and a primate find that life is no more excellent at court than in the areas, and in The Hind and the Panther (1687) John Dryden restored the monster epic as a metaphorical structure for genuine religious discussion.

The fable has generally been of unobtrusive length, in any case, and the structure arrived at its apex in seventeenth-century France in crafted by Jean de La Fontaine, whose topic was the indiscretion of human vanity. His first assortment of Fables in 1668 followed the Aesopian design, yet his later ones, amassed during the following 25 years, mocked the court and its civil servants, the congregation, the rising bourgeoisie-to be sure, the entire human scene. His impact was felt all through Europe, and in the Romantic time frame, his exceptional replacement was the Russian Ivan Andreyevich Krylov. The fable tracked down another crowd during the nineteenth century with the ascent of youngsters’ writing. Among the commended creators who utilized the structure were Lewis Carroll, Kenneth Grahame, Rudyard Kipling, Hilaire Belloc, Joel Chandler Harris, and Beatrix Potter.

AESOP’S Fables

Aesop’s Fables, or the Aesopica, is an assortment of tales credited to Aesop, a slave and narrator accepted to have lived in old Greece somewhere in the range of 620 and 564 BCE. Of assorted starting points, the tales related to his name have slipped to present-day occasions through various sources and keep on being revaluated in various verbal registers and infamous just as creative media.

The fables initially had a place with the oral custom and were not gathered for nearly three centuries after Aesop’s demise. At that point, an assortment of different stories, jokes and sayings were being attributed to him, albeit a portion of that material was from sources sooner than him or came from past the Greek social circle. The course of consideration has proceeded until the present, with a portion of the tales unrecorded before the Late Middle Ages and others showing up from outside Europe. The cycle is constant and people are adding new stories to the Aesop corpus continuously, in any event, when they are verifiably later working and once in a while from known creators.

Want To Know More?

Original copies in Latin and Greek were significant roads of transmission, albeit poetical medicines in European vernaculars in the long run framed another. On the appearance of printing, assortments of Aesop’s tales were among the most punctual books in an assortment of dialects. Through the method for later assortments and interpretations or variations of them, Aesop’s notoriety as a sensationalist was public news all through the world.

At first, the fables made their way towards the grown-ups and covered strict, social and political subjects. They were likewise used as moral aides and from the Renaissance onwards were especially utilizing it for the schooling of kids. Their moral aspect was built up in the grown-up world through portrayal in model, painting and other illustrative means, just as a variation to show and tune. What’s more, there have been revaluations of the importance of tales and changes in accentuation over the long haul.

Also, Read Using Props to make Storytelling Fascinating

First, we will be looking at the summary of ‘The Wind and the Sun’:

The North Wind and the Sun had a fight concerning which of them was the more grounded one of the stronger ones. While they were questioning with much hotness and rant, a Traveller passed along the street enveloped by a shroud. The Sun suggested that the one who can strip that Traveller of his shroud is the stronger one. The North Wind agreed, and immediately sent a chilly, yelling impact against the Traveller.

With the primary whirlwind, the finishes of the shroud whipped with regards to the Traveller’s body. Be that as it may, he promptly wrapped it intently around him, and the harder the Wind blew, the tighter he held it to him. The North Wind tore irately at the shroud, however, the entirety of his endeavours were in vain. Then, the Sun started to sparkle. At first, his pillars were delicate, and in the charming warmth after the severe cold of the North Wind, the Traveler loosened his shroud and let it hang freely from his shoulders.

The Sun’s beams developed hotter and hotter. The man removed his cap and wiped his forehead. Finally, he turned out to be warmed that he pulled off his shroud, and, to get away from the blasting daylight, hurled himself down in the welcome shade of a tree by the side of the road. The moral of the story is that delicacy and kind influence works in those places where power and force fizzle away.

The next story that we are going to take a look at is ‘Mercury and the Woodman’:

A helpless Woodman was chopping down a tree close to the edge of a profound pool in the backwoods. It was late in the day and the Woodman was tiring out. He had been working since dawn and his strokes were not entirely certain as they had been early that morning. Along these lines it happened that the hatchet slipped and flew out of his hands into the pool. The Woodman was despondent. The hatchet was all that was dear to him by which to get by, and he had not cash to the point of purchasing another one.

As he stood wringing his hands and sobbing, the god Mercury unexpectedly showed up and asked what the difficulty was. The Woodman determined what had occurred, and straightway the benevolent Mercury jumped into the pool. At the point when he came up again, he held a great brilliant hatchet. Mercury asked the Woodman if that was his hatchet. The fair Woodman addressed him and said that it was not his hatchet. Mercury laid the brilliant hatchet on the bank and sprang once more into the pool.

This time he raised a hatchet of silver, however the Woodman announced again that his hatchet was only a standard one with a wooden handle. Mercury jumped down for the third time, and when he came up again, he had the very hatchet that had been lost. The poor Woodman was exceptionally happy that his hatchet was there and could not thank the benevolent God enough. Mercury was significantly happy with the Woodman’s genuineness. The God respected the genuineness of the woodman. Therefore, he decided to give him all three of the tomahawks.

Conclusion

Along with the basic, wooden hatchet that the woodman already had, he now also had one made out of silver and one made out of gold. The glad Woodman got back to his home with his fortunes, and soon the account of his favourable luck was public news to everyone in the town. Presently there were a few Woodmen in the town who accepted that they could without much of a stretch success a similar favourable luck. They rushed out into the forest, one here, one there, and concealing their tomahawks in the hedges, imagined they had lost them. Then, at that point, they sobbed and howled and approached Mercury to help them.

What’s more, for sure, Mercury showed up, first to this one, then, at that point, to that. To everyone, he was showing a hatchet of gold, and everyone anxiously asserts it to be the one he misplaces. Be that as it may, Mercury didn’t give them the brilliant hatchet. God help us! Rather he gave them each a hard whack over the head with it and sent them home. Also, when they returned the following day to search for their tomahawks, they were mysteriously absent. The moral of this story is that saying the truth is always the best thing to do. Being honest is the only thing that can benefit us!

Here, we have come to the end of this article. It can serve as your perfect guide when it comes to anything related to Aesop and his fables. We have not only gone over who Aesop himself is but also his life, the meaning of the word fables, Aesop’s fables specifically and provided you with the summary of two of his most famous fables.

Also, Read Feel-Good Movies to Watch on a Lazy Day

Some Name of Fables

| SL No | Names Of Fables | Author |

| 1 | The Rivers and the Sea | Aesop |

| 2 | The Rose and the Amaranth | Aesop |

| 3 | The Satyr and the Traveller | Aesop |

| 4 | The Jar of Blessings | Aesop |

| 5 | The Mischievous Dog | Aesop |

| 6 | The Frog and the Ox | Aesop |

| 7 | The Bulls and the Lion | Aesop |

| 8 | The Hare in flight | Aesop |

| 9 | The Dove and the Ant | Aesop |

| 10 | The Fir and the Bramble | Aesop |

Frequently Asked Question (FAQs)

What is the meaning of Aesop’s fable?

A. Aesop’s Fables, or the Aesopica, is an assortment of tales, credited to Aesop, a slave and narrator who accept living in old Greece somewhere in the range of 620 and 564 BCE. Of assorted starting points, the tales related with his name were slipping to present-day occasions through various sources along with revaluating in various verbal registers and infamous just as creative media.

The fables initially had a place with the oral custom and were not there in hand for nearly three centuries after Aesop’s demise. At that point, an assortment of different stories, jokes and sayings were an attribution to him, albeit a portion of that material was from sources sooner than him or came from past the Greek social circle. The course of consideration has proceeded until the present, with a portion of the tales unrecorded before the Late Middle Ages and others showing up from outside Europe. The cycle is constant and people are adding new stories to the Aesop corpus, in any event, when they are verifiably later working and once in a while from known creators.

More About Aesop’s Fables

Original copies in Latin and Greek were significant roads of transmission, albeit poetical medicines in European vernaculars in the long run framed another. On the appearance of printing, assortments of Aesop’s tales were among the most punctual books in an assortment of dialects. Through the method for later assortments and interpretations or variations of them, Aesop’s notoriety as a sensationalist was there all through the world.

At first, the fables made their way towards the grown-ups and covered strict, social and political subjects. They were likewise used as moral aides and from the Renaissance onwards were especially utilizing it for the schooling of kids. Their moral aspect was built up in the grown-up world through portrayal in model, painting and other illustrative means, just as a variation to show and tune. What’s more, there have been revaluations of the importance of tales and changes in accentuation over the long haul.

How did Aesop get his freedom?

A. The legend tells it that Aesop resided during the 6th century BC, researchers have reduced his origination to maybe a couple puts however nobody knows without a doubt. He was a slave, and in the course of his life, two unique experts think that he possesses before conceding his opportunity. The slave drivers were Xanthus and Iadmon, the last option gave him his opportunity as an award for his mind and knowledge. As a freedman, he became associated with public undertakings and voyaged a great deal telling his tales ens route. Lord Croesus of Lydia was so dazzled with Aesop that he extended to his residency and an employment opportunity at his court.

What stories are Aesop’s Fables?

A. Some of Aesop’s fables are:

- Big Bad Wolf

- The Hare

- The Tortoise

- The Sun

- The Grasshopper and the Ants

- The Goat and the Vine

- The Goose that Laid Golden Eggs

- The Rivers and the Sea

Why does Aesop use animals?

A. No antiquated scholars assume of Aesop’s talking creatures as having anything by any means to do with genuine creatures. However, it is advantageous to think about why the tale went to humanized creatures for its central heroes. That is, we can consider the tale creature an especially early and dynamic launch of an antiquated distraction with following the limits among humans and creatures. The polysemy of the notable Greek origination of logos is fundamental here; it can signify (in addition to other things) “discourse,” “discussion,” “reason,” and (altogether) “story” or “tale.”

While the creature world was accepted to be administered by hunger and personal responsibility, people can utilize reason. Therefore, along these lines, they had to resolve clashes with discussion and shared influence. Aesopic tales play with the different implications of logos by having creatures utilize human discourse to speak to the laws and customs that administer human culture. As a rule, be that as it may, the creatures’ endeavours fall flat and give way to regular senses.

Why do fables have morals?

A. Tales are the ones that people describe through their ethical illustrations. These short stories were once passed down as fables to show audience members the distinction between good and bad. They offer guidance on appropriate conduct and habits, and proposition sayings to live by. One of the popular morals are ‘Honesty is the best policy.

To know more about Aesop’s Fables, you can read the tales by downloading this PDF!

Also, Read The Various Shapes That A Polygon Has And Its History!

Share with your friends